|

The following article appeared in the February 2009 issue of Banjo Newsletter.

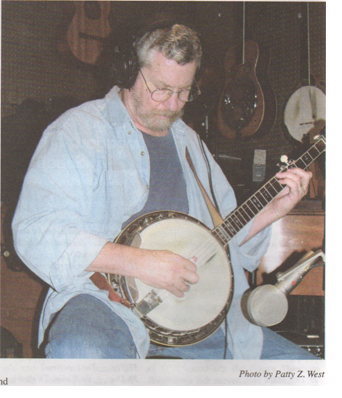

Take a well-known song like Stephen Stills' Love the One You're With. Remove textured vocals and replace with banjo, mandolin, guitar, and fiddle. Stir, bake and voila! Bluegrass magic. CMH Records has cooked up more than 100 Pickin' On's using this recipe, starting with "Pickin' On the Movies" in '93, followed by the first studio release, "Pickin' On the Beatles," in '94. They've 'picked on' anyone with a devoted following: the Grateful Dead, Led Zepplin, Pink Floyd, the Stones, Springsteen, Bob Marley, Boston, even Kid Rock, selling a total of 1.5 million records. Multi-instrumentalist David West, 56, who has produced more "Pickin' On" tracks (700) than anyone, initially converted his Santa Barbara home into a recording studio, unplugging appliances to reduce noise. His wife, art conservator Patty Zavagno, would return home to find water dribbling from the fridge. So West moved Studio Z (named after Patty) to a nearby commercial space, stocked with vintage instruments, tube microphones and preamps. He's heard snippets of his handiwork on NPR but also at surprising moments: he was on hold with a Bangalore techie and was tapping his feet before realizing it was one of his tracks. The son of an accordion teacher/exec and a piano-playing librarian, West eschewed the accordion for the guitar. Blame it on Beatle-mania. In 1972 he formed the Cache Valley Drifters, playing guitar in the band that backed singer-songwriter Kate Wolf. When the group folded in the '80s, West dedicated himself to the banjo. These days, West spends most of his time in the studio, when he and Patty aren't sampling art and music in different lands. They will visit Mongolia in '09. They love returning to idyllic Santa Barbara, but when wildfires raged in July, West had to evacuate more than 30 instruments from Studio Z. West plays most instruments on a typical "Pickin' On." But sometimes he'll bring in guest performers: Chris Hillman (mandolin), Doobie Brother John McFee (pedal steel), pedal steel legend Jay Dee Manness, or fiddlers Gabe Witcher, Richard Greene and Byron Berline. Lyndon Stambler: How would you describe the "Pickin' On" series? David West: We try to find music that people love and render it with bluegrass instruments. When I was with the Cache Valley Drifters, we used to do arrangements of famous songs. We'd start with a song and it would take the audience a second. Once it dawned on them what it was, a big old smile would come over their faces. They'd nudge their friends. That was the idea with the "Pickin' On" series. People would get a kick out of hearing songs they know done with banjos, mandolins and fiddles in adventurous arrangements. CMH had done a few before I came on, like the Beatles. After I did a few, I suggested they do one on the Grateful Dead. The three volumes I did sold 71,000 copies. That funded my studio. At that point I got really serious about recording rather than gigging. BNL:How do you convert a popular song into a "Pickin' On" track? DW: First I sit down with the song, say Box of Rain by the Grateful Dead. When I was 18, I absolutely loved the album it was on, "American Beauty." It's a great song, musically interesting, the words are cool and abstract. But it's in a beat that doesn't translate to bluegrass. If you double-time it, it will be way too fast to play and if you don't, it will feel too slow. In this case I made the bluegrass instruments fit the song rather than make the song fit the instruments. I sped it up a bit. It's more of a country style than bluegrass. It's got drums and electric bass and electric guitar and fiddle. So I listen to the song. I figure out what key it's in. I make a chart of the chord changes. I don't read music so the chart isn't note specific. All it needs to do is show me the chords and the timing. I'll usually start with a click track. I'll find a drum machine sound that has the feel. I'll lay down a rhythm guitar part and electric bass, which may or may not get used. In case it does get used,I make sure that every downbeat has a corresponding bass note and that there is no space between them. They're just dead on. That becomes the basic song. Then I start layering arrangements. The first verse may be a guitar solo, so I'll play that. Then where the guitar or the banjo or the mandolin trade licks, I'll lay those down one at a time. About a third of the way through, I stop telling the song what it wants and it starts telling me. Maybe this next verse ought to be fiddle with a nice harmony part with another instrument. I don't play the fiddle, so I'll call someone in. Few people play fiddle as well as Gabe Witcher. The song might say this electric bass is sounding like it should be acoustic. I'll replace it with a string bass. The same thing with guitar. Or I'll think, 'Is this starting to have more of a Bakersfield honky-tonk sound?' if so, the last thing I do is bring in a drummer who will listen, make his own chart, sit down and play. BNL: How did you get into music? DW: My dad was the vice president of the Milton Mann Accordion Studio, which had 25 locations throughout Southern California. He worked for them into the '70s. My mother played the piano and was musical but not professional. My sister and brother went through the accordion school. By the time I was nine, the Beatles had come along. I didn't want to play accordion. I wanted to play guitar. My older brother brought home guitars, banjos and mandolins. I learned to play guitar and string instruments by ear. I don't read music notation very well. I'd prefer that was otherwise. BNL: When did you first hear the banjo? DW: The Dillards were on several episodes of the Andy Griffith Show and played the part of a hillbilly family that lived way up in the mountains and played bluegrass and made moonshine. I loved Doug Dillard with his deadpan expression and mouth hanging open playing ripping 5-string. It was nothing like the guitar although it was a stringed instrument. It was a strange instrument. I later became enchanted with it when I paid attention to how it developed, the unusual way it's played with that fifth string on top, and how Earl Scruggs transformed it. I was a guitar player until my 30s. Although I plunked around on banjos, I didn't have anyone to teach me. I didn't know how to make it sound the way Doug Dillard made it sound. By my 30s, I had played guitar in bluegrass bands, but I knew enough about the way the banjo was supposed to sound that I figured it out on my own. BNL: What kind of banjo did you get? DW: My first banjo was a one-of-a-kind Garape, which I bought for $150. He made banjos from found parts. He had all these goofy ideas. He'd get tuners from wherever. Some were arch-tops and some were flat-tops. All of them were pretty darn good. I wish I had my old banjo. I never played it much. I couldn't figure it out. I sold it to somebody. In the '80s I bought a knockoff of a Gibson for $300 or $400 that was made by banjoist John Hickman. That's when I started to learn. BNL: Do you play banjo like a guitar? DW: No, I play it like a banjo. BNL: But you came to it from a guitar background. DW: Yeah, I'm a finger style-guitar player but if you try to play banjo the way you play finger-style guitar it doesn't make sense because of that high string. You can't Travis pick. Probably the most important thing I've ever learned on the banjo was the reverse roll. That snapped everything into place for me. Once you learn this simple roll you can play through any bluegrass song. Just change chords when the chords change and keep that roll going and you'll be right on beat. It's symmetrical. All of a sudden it's sounding like a banjo and not a guitar-player playing banjo. From there you start to hear deviations. You'll be able to work those into your style. Since the mid '90s the banjo has been my main focus. Of all the recording sessions that I get as a player, I probably get more for being a banjo player than anything else. It baffles me because there are a lot of great banjo players around. BNL: Have you learned banjo licks by slowing the music down? DW: I've never learned other people's solos or by slowing things down. What has been far more important to me, for better or worse, is getting the feel of something more than the note for note articulation. I just want to impart this feel of the driving banjo. Now that I've been doing this for a long time my banjo playing has expanded both ways: closer to the way Earl Scruggs played than I used to be and closer to the more modern melodic stuff and the jazzier stuff like Béla Fleck. Lately I've been paying a lot of attention to the way Don Reno played with that single string. BNL: What were some of your first musical influences? DW: When I was young, the country was experiencing what has been called the folk boom, or the folk scare because it coincided with the red scare. It wasn't necessarily music of the people. You had groups like the Kingston Trio, Peter Paul & Mary and these strange conglomerations like the Christy Minstrels singing In the Pines. It was a little silly. Of course it opened doors to the real thing. I looked around for the sources of that music. When I was a teenager I was a big fan of the Grateful Dead. Everyone knows the Dead as a rock band, but their influences go back to bluegrass. Garcia was a great banjo player. In the '60s he went back east to all the festivals and really learned to play. All those guys blend a lot of musicological boundaries into an intelligent blend, not just a naïve blend. It helps if you know the tributaries that lead to these different styles. BNL: How did you become a professional musician? DW: When I was at Santa Barbara City College, I started the Cache Valley Drifters and my interest in music eclipsed my interest in being in school. I figured I could earn some money playing music and that's what I did. It started out with me and Cyrus Clark in 1972. It was a progressive style bluegrass band. We purposely didn't do the old bluegrass repertoire because we wanted to do original songs and complex arrangements of songs.

BNL: How did you start playing with Kate Wolf? DW: We got to know Kate when we played in Sonoma County. She recorded two songs that I wrote with Cyrus Clark and had me play guitar on her first album. I suggested that it might be good to have the whole band back her up for her second album. She had a mobile recording truck come out to a farmhouse in Bodega Bay in Sonoma County. We'd stay there for a week or two and record. She wrote everything from the heart and did not get bogged down by embellishment. Less is more. BNL: When did the Cache Valley Drifters disband? DW: In 1983, but we would get together for an occasional gig. I started playing banjo in the Drifters in the late '80s. In the mid-'90s we recorded a reunion album called "White Room" on CMH Records (released in '96). I developed a nice rapport with Martin Haerle, who was the owner of CMH. That began my association with CMH as a staff producer and led to the "Pickin' On" records. After Martin Haerle died, his son David took over the business. I had worked as a producer, but I got really serious about it with the "Pickin' On" series. By the late '80s the bottom had really fallen out of the gigging thing. I was lucky I had an interest in recording and the support of CMH. I ended up doing 50 or 60 albums for them and then they spun off another 20. They would take hot banjo tracks and put them all on one. BNL: Do you have any favorite "Pickin' On" albums? DW: One of my favorites is "Pickin' On the Grateful Dead Vol. 2." Everything came together: the players, the arrangements, the sessions. It's fun and easy to listen to. There's nothing I want to fast forward through. Sometimes, even when a song comes out well, if the session was difficult it colors my image of it. That one was a delight. Another one I like is "Pickin' On John Mayer Vol. 1." The arrangements were pretty difficult because it's complex music. Making charts of John Mayer's songs is a challenge. BNL: How so? DW: John Mayer's songs are sophisticated in a harmonic sense. He uses a lot of extended chords. It's not just G, D and C. There are a lot of minors, major 7s, add 9s. His progressions go all over the place. Of course, there are a lot of people that get even weirder. When I first started doing it, David Haerle and I would sit down with an artist's music and we would rate songs as to relative ease or difficulty to convert them into bluegrass. Then we'd carefully pick the song. By the time the series got going, he would say, "Pickin' On Pink Floyd." They'd send me a bunch of songs. It became quite a challenge but that was the fun of it: turning unlikely bluegrass material into something that sounds good with banjos, fiddles and mandolins. It takes a certain amount of ingenuity to do it. BNL: BNL: The lyrics often make the songs and you're dropping the lyrics. DW: True, but most people who buy "Pickin' On" records were such fans of, let's say Bob Marley, that it will be fun to hear them with banjos and fiddles. You can't forget the main feature of "Pickin' On" records is hot licks and fun listening. If you know the songs, so much the better. But it shouldn't stand on the presupposition that you know the song. For "Pickin' On Bonnie Raitt" I did one of her gorgeous, sad ballads, I Can't Make You Love Me. Even though I picked it up and did it with a Travis- style guitar, I like to think I captured the pathos of the song. It's still pretty and emotional but there are no lyrics. BNL: Do you hear the music on the radio? DW: You hear it on NPR between segments of All Things Considered. They use snippets when they need to fill 17 seconds. That's led to a lot of sales. I was recently on tour and driving around Kalamazoo, Mich. I turned on the radio and boom, there's something from "Pickin' On Crosby Stills & Nash". I've seen the records everywhere: Africa, Australia, Europe. Almost any bluegrass group would kill to sell 10,000 records and many of these "Pickin' On" records sell at least that many. "Breathe: The Bluegrass Tribute to the Dave Matthews Band Vol. 2" sold 12,000 copies. ["Pickin' On the Eagles," not produced by West, is the best-seller for CMH with a total of 85,000 sales.] BNL: People are devoted to him. DW: The same thing with Jimmy Buffett, the Grateful Dead, Neil Young. CMH does demographic research. There were a few I've suggested, and because I have a good track record, they let me do it. I did a nice one on the Byrds. Although it was one of my favorites, it didn't do well. BNL: How did you get Roger McGuinn's Rickenbocker guitar sound? DW: I tuned my mandolin in octaves. I took the low G-string and replaced it with one that's an octave higher and replaced the D string with an octave higher, so it had a 12-string sound. I did a Van Morrison one that I thought was a beautiful record. It didn't set the world on fire until a friend of mine who belongs to a Van Morrison online chat did a review. It's been selling steadily since. BNL: What responses do you get from bluegrass purists? DW: You could probably imagine that not everyone is thrilled. But sometimes the best support comes from the least likely places. Bluegrass Unlimited is a conservative bluegrass publication and yet they have given us really good reviews. Bluegrass traditionalists who really like the old style repertoire are a little resistant for a number of reasons. One is that although it's advertised as bluegrass music, CMH lets me interpret bluegrass very loosely. If you just use banjo, guitar, mandolin, bass and fiddle, it would be hard to get enough variation to keep it interesting. So they let me use piano, electric guitar and drums, horns, pedal steel guitars, hammer dulcimers, and bongos because musically and sonically it works. Even the traditionalists realize that if this many people are buying these records, maybe they're going to find Bill Monroe or Flatt & Scruggs. BNL: Have you had other banjoists besides you play on it? DW: If there is something I can do, it's cheaper for me to do it than to hire someone else. That's why I generally play guitar, banjo, a lot of mandolin and bass, and a few other things too. BNL: How do you play the banjo on these "Pickin' On" albums? DW: I figure out the solo on the spot. The clock is ticking. When you consider that I've got to learn the stuff and arrange it and figure out what to play on four instruments, it doesn't leave much time for anything. BNL: What kind of banjo do you play? DW: I have two banjos. I've had a Bob Givens flat-top banjo for 20 years that was a conglomerate of various parts. Bob made the neck out of flame maple. It says Gibson at the top and "R.L. Givens" by the heel block. Ren Ferguson made the wooden shell. Chuck Ericson supplied the rest of the parts: the tone ring, tension hoop, flange, tension hooks. The banjo I've been playing mostly for the last few years is a TB-3 tenor banjo. It started out as a 1927 Gibson tenor banjo with an arch-top. I had a 5-string neck made by banjoist Larry Cohea in San Francisco. He made an exact knockoff of the four-string neck with the same old Gibson inlays on a rosewood fingerboard. I always wanted an arch-top banjo because that's what Doug Dillard and Ralph Stanley play. I wanted something that sounded different from my flat-top. So I bought it and had it converted into a 5-string. It's turned into my main banjo. It has a great, ringy, bright sound. BNL: When you go on tour what instruments do you bring? DW: Generally, I bring a guitar, a mandolin and a banjo. I was just out in the beginning of June with Peter Lewis who is famous for being one of the principals in the rock group Moby Grape. It's just the two of us. Peter does his thing and I back him up with whatever seems appropriate. I played on several of his records so I know the parts. I do the same thing occasionally with Chris Hillman. There's a terrific songwriter in Santa Barbara named Kate Wallace with whom I play. I play regular bluegrass gigs with a fellow up here named Peter Feldman. He's a serious folk musicologist and a terrific Bill Monroe-style mandolin player. He knows all the traditional, deep dark gothic bluegrass stuff that I scanned over when I was younger. Now I'm going back to it.

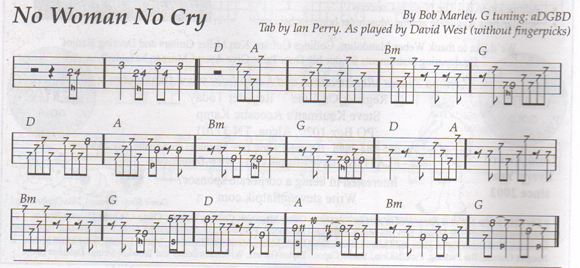

David backing up Chris Hillman of the Byrds BNL: Who is your favorite banjo player? DW: It's hard to narrow it down. Some of my favorites include Bobby Thompson, Herb Pedersen, Dennis Caplinger, John Hickman, Alan O'Bryant, the Great Earl Scruggs, Ralph Stanley, J.D. Crowe, Tony Trischka, Noam Pikelny, Alan Munde, and groove guy Bernie Leadon. Béla Fleck has transcended bluegrass. He knows the bluegrass repertoire inside and out. He's conversant in jazz and classical. The thing that's so amazing is that when he plays jazz it sounds right on the banjo. Sometimes when I hear people play jazz on the banjo I go, 'That's really great but it would just sound better on a guitar or a horn.' You never think that with Béla. That's part of his genius. It's not just knowing the music but being able to make it blend and sound right. BNL: What qualities do you bring to your banjo playing? DW: I've always been more concerned with the overall piece of music than my performance as a banjo player, guitarist, or bassist. If it requires hot licks, I'm happy to do that. But mostly what songs require are for you to be in time, in tune, and, above all else, to groove, so that the song pulls you along and there's an effortlessness to it, not something that tears and tugs. BNL: Do you have a favorite song that you've done that features banjo? DW: On "Pickin On Jerry Garcia" I did a nice solo banjo version of the song Smoke Gets in Your Eyes. There's a song called Foreplay on "Pickin' On Boston." It's a Bach-like fugue. BNL: How much time do you spend practicing the banjo these days? DW: Regrettably not that much because I'm pretty much playing sessions all day and night. People send me tracks and say play banjo to this. I just sit there with the microphone on and just roll it and play to it.At the end of it I listen to it and I go, 'Well, that's okay but it needs to sound better. People are going to spend money on this.' I try a million different things: unlikely things, cliché things. When I'm done with it, I just want it to sound good. BNL: What challenges do banjo players face in studio work? DW: Just making a banjo sound good is probably the biggest one. But to be serious about it, I don't know if it's any more than any other instrument. When you make a recording, you have to sound good. I'm the first to admit that I don't always sound good on every recording. There are things I listen to and I shake my head and go, 'I wish I had spent another 10 minutes with microphone placement on that song.' But with budget and time constraints sometimes you just can't. In a perfect world I like to take the time to find the place where the banjo, or whatever instrument I'm playing, sounds best through a microphone and get that tone sounding as natural as possible. BNL: Do you use tubes or solid-state mikes with banjo? DW: With the banjo and the mandolin, oddly enough, I don't use tube microphones. I use solid-state mikes because they have a bright and quick response. Tube mikes are a little slower. With guitar I generally use tube mikes and preamps. Certain instruments are suited to certain mikes. Then those rules change depending on the application: what kind of song it is, where the instrument fits in the mix. Some mikes bring an instrument right out front. Others put it nicely in the back where you can still hear it but it's not dominating. These are the kinds of decisions you learn to make when you start producing and engineering records. This is precisely why when CMH asked me to do the first "Pickin' On" records that even though the budgets were small, it forced me to make these decisions quickly and to learn about the tools in my toolbox. BNL: What kind of budget did you have for the "Pickin' On" CDs? DW: Let's just say it was enough to do it. It wasn't enough to hire a lot of people, so that's why I played a lot of parts myself, which I really enjoy. But it was enough that I could occasionally hire someone like Albert Lee. Some of my absolute heroes got to be on these records. The attraction was on the royalty end. If the record sold well, you would be rewarded on the back end. It worked out pretty well. BNL: That's rare. DW: CMH is an upstanding and honest company. That's the people I like to work with. BNL: Do you use computers in your recording? DW: Analog and then ADAT were popular 10 years ago, but Pro Tools is such an amazing system that I'll probably never go back. The computer way has come so far with the sound. If you're on a deadline, it makes all the sense in the world. BNL: Do you write many songs? DW: In my youth I did because we had to keep coming up with records full of original songs. I found that I could write a pretty good song. I wrote about 25 or 30. I wrote one of my favorites about 10 years ago called Miles from Nowhere when I was in East Africa. It's on my solo album, "Broken Down Believers" (Germany's Taxim Records). I have another solo album called "Arcane," which is on Taxim in Europe but also came out in the States on Sage Arts Records (Seattle, Wash.). I have a solo record called "Off the Rails" which Fire Heart Records put out a couple of years ago when I was phasing out of doing "Pickin' On" stuff. I looked at hundreds of tracks and picked 12 that flowed together well. BNL: Have you learned any lessons from making "Pickin' On" albums? DW: I almost didn't do it. When they first asked me I declined. They called me back and said, "We have an emergency. We really need to do this thing." I had a couple of weeks off so I said, "Okay, I'll do it." That 10 years I did "Pickin' On" albums was one of the richest times of my life. It paved the way for what I'm doing now: TV commercials and television show backup music. I'm producing a lot of singer-songwriters. I can do the gigs I really want to do. When I go on the road, it's pure fun with people whose music I love. Making that first "Pickin' On" album was a turning point for me. BNL: Any advice for budding banjo players? DW: Do all the things I didn't do. Learn to read. I guess tab is pretty helpful. I was never much of a left-brain guy. Reading tab seemed to be counter-intuitive to playing music to me. But if there's any banjoist out there like me who is a right-brain guy who loves to hear music and play it, that reverse roll was a really important thing for me. BNL: What else would you like to say? DW: I've played a lot of different kinds of music and I love it all—western swing, blues, reggae, country, Irish music, solo guitar instrumentals. My favorite thing to do when all is said and done is to play banjo or whatever they want me to play in a bluegrass band. Four or five guys with as few mikes as possible, preferably one mike and everybody gathers around. Even if you're playing that same old repertoire of bluegrass standards, it's just a kick and I love it.

Lyndon Stambler has interviewed Herb Pedersen and Kevin Nealson for BNL, and also co-authored "Folk & Blues: En Encyclopedia." He teaches journalism, and free-lances for various magazines.  David backing up Peter Lewis of Moby Grape, Los Angeles |